Regardless of whether we were anchoring with the Bruce or the Rocna, we went about dropping and setting the hook in the same fashion. We honed our routine slightly as the summer went on, but, for the most part, Margaret and I anchored the same way that we have on charter boats and, for that matter, the same way I did on my Catalina 22.

We start by circling the anchorage. I have nothing against entering the harbor and immediately dropping the hook if we are comfortable with the situation. But the reality is that coming into a new spot, or even a place we have been before, there are usually a few things we need to figure out. Slowly weaving in and out of a few boats, we can assess where there is a space large enough for us to set the anchor and let out enough scope to feel secure. Along the same lines, we also look at the rodes of other boats, noting whether they are chain, like ours, or rope, which will cause them to swing more regularly and at slightly different angles than us. This is especially important for us on Bear because with our full keel we tend not to ride as much at anchor as most other boats already do. If we are concerned about depth at all, we also do a little underwater reconnaissance, noting the contour of the bottom with our depth finder, as we case the anchorage. This became increasingly important as we headed further south into South Carolina and Georgia. With tidal ranges of up to nine feet, a place that appeared, at high tide, to have more than enough water could easily have us aground six hours later.

After we found a location that we thought was acceptable, I often took the helm and reduced speed by reversing, so that we were just ever so slowly creeping up on our desired location. Ideally, I would have us at rest right where we planned to anchor, hand the wheel over to Margaret, and go forward to drop the hook. Occasionally, I would think – or hope – that we were in the right spot and not making way, only to go forward and, while loosening the clutch on the windlass, realize we were moving out of the place we had intended either because I had not fully stopped us or because the wind or current had already begun acting on us. In that case, I would just loosely engage the clutch again – so I could drop the hook quickly the next time around – and return to the helm for another try. While I never feel very salty having to circle the anchorage again, there is nothing so uncool as dropping the hook and having to pick it up and reset because I misjudged the situation. You might also be wondering why I do the steering in most cases; though Margaret is fully capable of doing so, she prefers that I put us on our desired spot given my neurosis regarding anchoring (basically, having me solely responsible reduces tension aboard).

Once we have the boat over the perfect location, I let the anchor chain run out to between one and one and a half times the depth of the water. So, if we are in fifteen feet, I will try to let out about twenty feet of chain, which is easy to judge on our boat because I have marked the chain every twenty feet (incidentally, we replaced our initial wire chain marks with bright orange spray paint while in Annapolis, making them far easier to see). I then give the signal to Margaret – we have a well-developed sign language that we are quite proud of – to ease Bear into reverse. As the boat begins to back and put the slightest tension on the chain, I start to play out more rode.

When I have a scope of about three to one, I again engage the clutch, stopping any more chain from going out. At this point, I like to let the anchor grab the bottom a bit. With the Bruce, there was about a fifty-fifty chance that the anchor was just going to skip across the bottom at this point. But with the Rocna, the anchor always bites in, arresting the boat’s progress in reverse. After a few more seconds of just pulling against the anchor, I let our more chain at 10 to 20 foot intervals, making sure I do not pile the chain on the bottom, until we have sufficient scope.

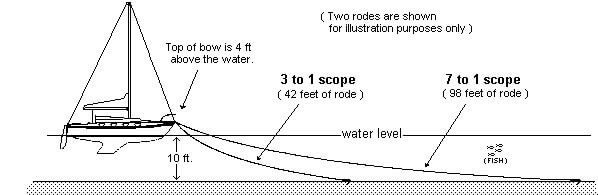

Deciding what is enough scope is always particular to the circumstances. I never like to have less than five to one scope out, but we have, on two occasions, in the tight confines of Baltimore’s Inner Harbor and Fogg Cove off St. Michaels, had as little as four to one. If there are few boats around us, I will put out 7 to 1. And, if we have any threat of squalls, I will even let out as much as 10 to 1. When calculating our scope, we always add four feet to the depth of the water to account for the distance from the end of our bowsprit to the waterline, which affects the angle at which the chain comes up from the anchor. I also consider the fact that we will be putting out 15-20 feet of a rope snubber after we are completely set, increasing our scope that much more. Finally, we always take into account the tidal range in our calculations. For example, if it is mid-tide in an area with eight feet of tidal range, we will add four feet to our depth in determining the scope.

A great illustration of scope from Go2Marine.com

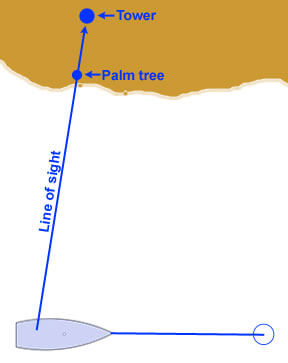

With enough chain out, I then attach a line (which I will discuss the particulars of tomorrow when I detail our various anchor snubbers) from the Samson post to the anchor chain and pull another couple feet of chain out of the locker so that the line and the post, not the chain and the windlass, is taking the pressure from the anchor. Returning aft, Margaret begins to increase the power in reverse as we both take ranges on two objects on shore so that we can determine whether we are moving. If we are at all far from shore or are in a place – like a scheduled marsh anchorage – with nothing to align for a range, I will use the chartplotter to ensure the anchor is set. I just make a waypoint where we are and then zoom in all the way and monitor our distance from the waypoint. We will often move a couple feet from the waypoint as we take the catenary out of the chain or pivot slightly on the anchor. But, it is clear that the anchor is not set if our ranges move out of alignment or the chartplotter shows us slowly distancing ourselves from the waypoint. Once we have the engine up to about 2600 rpms, we will sit there with full pressure on the anchor for a minute or so while we watch closely and make certain that both of us are assured we are not dragging. Once we are confident in our set, we ease back on the engine, let it idle for a couple minutes while we are tidying up the cockpit, and then finally turn it off and enjoy the blessed silence. Our final step in the anchoring process is to attach a longer rope snubber to the anchor chain and let it out along with additional chain so that, again, the pressure from the boat at anchor is on the snubber and Samson post rather than the windlass.

A good illustration of taking a range from Schoolofsailing.net

You can see our previous posts on our initial ground tackle, adding a Rocna anchor, and our experiences with the Rocna.