For those of you uninitiated in the ways of online cruising message boards, there are two things that start an argument every time: guns and anchors. Obviously, there are folks who are pretty passionate about firearms, but I bet few of you realize just how fanatical people can get about not just their own anchors, but other people’s as well. However, after you have spent a little time on the water, the obsession with anchors, anchoring, and ground tackle makes a little more sense. After all – as I am fond of telling people who come aboard, but not so enamored with thinking about myself – a fifty-five pound hunk of metal holds our 24,000 pound vessel in place. While cruisers obsess over a lot of stuff, very little is as directly related to the safety of your boat and crew on a daily basis than your anchor, ground tackle, and ability to put them to use.

When we purchased Bear, the anchors were something that we paid a lot of attention to. Before buying the boat, we were happy to see it had a 44-pound Bruce as its primary anchor, a large Danforth on the bow, and a 35-pound CQR in the lazarette. About twenty years ago, this collection represented the state of the art, and it still is not a bad group of anchors. The Bruce is a patented claw-style anchor. When Peter Bruce invented it in the 1970s, it seemed revolutionary, offering more holding power and a quicker set than most other anchors available. A mathematician patented the plow-style CQR back in the early 1930s, but I do not believe that anchor became all that popular until the 1960s and 1970s. Like the Bruce, the CQR offered a big improvement over older style anchors in most conditions, resetting fairly easily and digging into a variety of bottoms. The Danforth, a fluke-style anchor, emerged in the 1940s and has been a favorite for use in sand and, especially, mud. But the Danforth is particularly poor in weed, often kicks out during a wind or current change, and has difficulty resetting. With these anchors, we imagined we would be fine, though we did intend to purchase a new generation anchor to serve as our primary anchor in a couple of years.

We did not examine the rest of the ground tackle as closely as the anchors, though we should have. However, we knew there was an all chain rode on the Bruce and a second rope rode with about ten feet of chain leading to the Danforth. Both rodes fit into the anchor locker, passing through a hawse pipe to the windlass above. The windlass, which turned out to be an older Lighthouse 1501, looked to be robust and well maintained. In all, we were happy with the available equipment and its condition and appreciated the evident thought that had gone into its selection.

Our bow sprit with windlass and Danforth. The Bruce is out on the floating dock to the left of the picture.

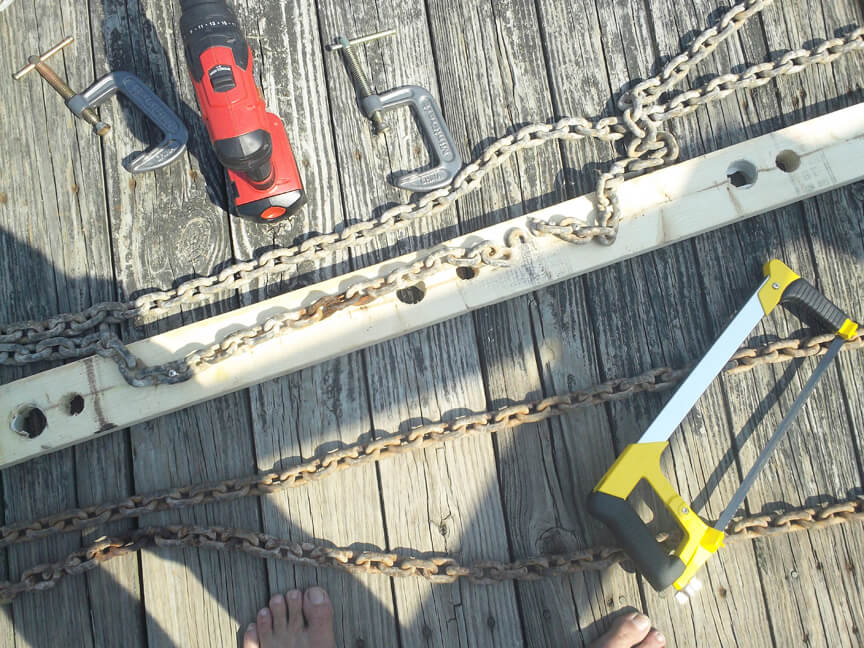

Once Bear was in the water, but while we were still at the dock in Branford, we pulled all the chain and line out of the anchor lockers to check their condition. While we had the rodes out, we also intended to mark them every twenty feet so that we would know how much chain we had deployed while anchoring. The line on the Danforth appeared to be in good shape and was already marked with nifty plastic tags. The 5/16th inch chain, on the other hand, appeared a bit rusty with one short section in the middle looking like it was close to rusting through. At first, we decided to cut the 200 feet of chain in half and attach a 100 feet of line to the slightly longer section. After accomplishing all that, however, I still had some misgivings about that setup, not least of all because it would have been a struggle to get the rope-line connection through the hawse pipe. When Margaret, probably realizing it was not going to be fun having me worrying about the anchor setup all summer, suggested we replace the entire chain, despite the nearly one thousand dollar cost, I jumped at it.

Setting up the new chain was fairly easy. I started by stretching the chain out on the floating dock and marking it every twenty feet. Then, I attached the chain to the Bruce with a new anchor shackle, mousing the pin of the shackle with stainless steel wire

. Finally, I connected the bitter end of the chain to the stem of the samson post, tying a line to the post and then braiding the other end of the line through the chain before tying a hitch to fully secure it. Should the full 200 feet of chain ever play out, the idea is that this line will make certain we do not lose our ground tackle. At the same time, should we need to slip our anchor quickly in an emergency, we can just cut this line rather than have to struggle with a shackle. Storing all the beautiful new chain in the anchor locker, I felt really comfortable with our ground tackle.

During our first two months at anchor in Long Island Sound and the Chesapeake, we never dragged. However, we often did have difficulty initially setting the anchor. We would drop the hook, slowly let out chain until we reached our desired scope (the ratio of chain to depth), and then slowly back down on our anchor using the engine at 2600 rpms. Nearly every time, it would take us two or three tries before we got the anchor to stick, as it started to slowly drag as we throttled the engine above 2000 rpms. This was time consuming and, especially for Margaret who would handle the wheel through it all, stressful. In the worst instance, we could not get either the Bruce or the Danforth to hold during five attempts in the soft mud of Hempstead Harbor.

Eventually, our problems setting the hook led us to purchase a Rocna in Annpaolis, which I will discuss next time. I will also post a detailed description of our anchoring technique, the snubbers we use, and our nastiest storm at anchor.

Which mathematician?

Sir Geoffrey Ingram Taylor is the guy. What should the rest of us know about him, Dan, other than that he was a dedicated sailor?