This is the fourth in a series on my 2011 trip to the Chesapeake aboard my Catalina 22, Helbent. Here are the first, second, and third posts.

It was only fifty degrees, so I dressed warm while I was still trying to wake up after the 3 am alarm. The thought did cross my mind for half a second that it would be a lot easier to get back into bed, go on a shakedown sail later in the day, and depart the following morning. But I quickly put those thoughts aside and, with a mixture of excitement and a dash of trepidation, double-checked that I had the charts, GPS, VHF, and a few other last minute items I had gathered the night before.

Though my folks rental was just two very short blocks from Helbent, I took the car because I wanted to stop at Wawa before setting sail. For those of you who have never had the good fortune of experiencing a Wawa, it is a delightful convenience store chain with exceptional coffee and an excellent, inexpensive deli counter. Stretching from Flemington, New Jersey to Richmond, Virginia, they are now opening outposts on Florida’s west coast too. I long for the day when Wawa has taken over the world. With a large decaf coffee (to save the effects of caffeine for later in the day, if necessary) and two veggie classics for breakfast and lunch, I was on my way to the club.

Getting out of my car at the club, I could see the north wind pushing Helbent against her fenders alongside the floating dock. The breeze was a little stiffer than I imagined it would be – a steady 15 knots – but I was comforted by the marine forecast indicating that the wind would slack some by dawn. Without anything left to do, I donned my headlamp, flicked on the newly installed nav lights, started the engine, and untied the lines. It was an uneventful start to what would be a memorable day.

Just a few moments later I had cleared out of the yacht club basin and headed the boat into the wind. Scrambling to raise the main before the boat came around again in the relatively tight channel, I had a half second of terror realizing I had not even raised the main yet that season; doing it for the first time in the dark, just a couple hundred yards from a lee bulkhead, in a narrow channel with the tide coursing through was not my best moment of prudent seamanship. Thankfully, I managed to get the sail up, turn off the engine, and partially unfurl the jib without a hitch. It was the first incident of what would become a recurring theme of the day: though cruisers always say at some point in time you just need to cast off the lines without completing everything on the punch list, there are certain basic things that should be in working order and thoroughly tested and trusted before leaving the dock…and the mainsail and rig should probably be at the top of that list.

The rest of the sail down the intercoastal to the inlet was wonderful. A full moon shone brightly to the south, giving me just enough light to pick out the markers as the outgoing current helped push me along at 5-6 knots. The first hints of dawn emerged as I was just getting into the wildlife refuge on the south end of the island, leaving the houses and lights of shore behind. By the time I rounded the southern tip of the island and entered the inlet, the full moon was setting over Brigantine as the sun peeked above the horizon to the north of east. Tears came to my eyes at the beauty of it all and the excitement of the trip, and the whole scene immediately brought to mind the end of Pat Conroy’s beautiful novel, The Prince of Tides:

The sun, red and enormous, began to sink into the western sky and simultaneously the moon began to rise on the other side of the river with its own glorious shade of red, coming up out of the trees like a russet firebird. The sun and the moon seemed to acknowledge each other and they moved in both apposition and concordance in a breathtaking dance of light across the oaks and palms.

Yes, I had returned to the sea, but not from prison, like Tom Wingo’s father, just from Arkansas.

Entering Little Egg Inlet in the dim light, I could not make out the next channel marker. For those of you not familiar with this little patch of water, there is a marked channel that winds its way towards Brigantine to the south and then east to the bell buoy. In calm seas you can head south earlier without incident, but you do need to steer clear of any hint of cresting waves and stay in the channel until you are at least a half mile or so out the inlet. There is another unmarked, narrow stretch of slightly deeper water that hugs the southern tip of Long Beach Island, called Beach Haven Inlet. While the unmarked inlet would seem more dicey, I have probably gone out of it twenty times for every one time I have exited through the marked channel. So, in the early morning light, I decided to head out the north entrance. Obviously, in any inlet but my home one (and maybe even in that one I should have been more prudent), I surely would have waited another twenty minutes for more light. Instead, I sped out on the outgoing tide and was quickly clear of the shallower waters.

The yellow line is roughly Beach Haven Inlet while the red is an approximation of the marked Little Egg Inlet. From Google Maps with my great artistic additions.

As I headed farther offshore so I could avoid the breakers to my south, I fired up the GPS, looked up the heading from the Little Egg to the Absecon bell, and did the easy math to figure out the magnetic course. Later in the trip we would keep the GPS on whenever we were underway, but at this point I not only had no idea how long the batteries lasted, but I also wanted to see how well I would do at steering a compass course. Giving the shoals a wide berth, I rounded south and left the Little Egg bell buoy behind. Just as the marine forecast had suggested, the wind had slackened to a perfect 10 knots with an easy sea coming from the northeast. The clear, placid sunshine reminded me of July or August, but I was still bundled up in pants, jacket, and winter hat on this early June day.

Two hours or so later, the Atlantic City bell rose out of the water in front of me, two dolphins came alongside to say hello, and the casinos stacked up along the shore. I called my Dad on my cell phone, ate the first hoagie and a grapefruit, and checked the heading (which I had now realized/remembered was conveniently printed on the map) to Great Egg Inlet. Most of the rest of the day continued without incident. “Real” cruisers passed me heading north to Long Island Sound and points beyond for hurricane season while I continued to make headway southwards, passing Ocean City, Sea Isle City, and Avalon while noting each new bell buoy as a milestone.

At Townsends Inlet, I decided to head a little further offshore because the rhumb line course took me fairly close to the shoals off both Avalon and Hereford Inlet. It was about this time that the wind kicked up again, building over the course of the afternoon as I incrementally reefed some of the jib. It was also around this point when I noticed that my lower forward shroud on the port side was fairly loose. Not being able to tie off the helm very effectively, I watched it, but recall thinking there was not much I could do about it. Of course, in hindsight, I realize that I was acting like a complete moron; I could have easily heaved to for a few moments or even just luffed up while I ran forward to check and tighten the turnbuckle. But somehow, out in the ocean, by myself, with a rising breeze, I somehow thought it was not only alright to “just keep an eye on it,” but that it was actually the safer option. And so this could be reminder number two about being more fully prepared before heading out and would, eventually, reinforce an equally important lesson about regularly checking and immediately fixing gear and rigging while underway.

Before too long, the breeze had built to a steady 20 knots and shifted about 90 degrees to the west. What had been a pacific, near downwind run, had become a beat into an increasingly choppy sea. Combine the wind shift, wave action, and fact that I had purposefully headed further offshore, and it became apparent I would need to tack into the coast to enter the Cape May Inlet. And so began a two hour upwind slog that just a half hour before had appeared to be an easy sail of half that time. But before long I started to make out the narrow inlet, guarded by long jetties on either side and bustling with commercial fishing, Coast Guard, and recreational traffic, including large head boats that seemed to be parading home at the end of their day trips. The swell from the northeast was still running and the chop from the east had worsened, making me a bit worried about how the outboard would handle it all. So, I got as close as I dared before furling the last of the jib, starting the engine, and bringing the main down in the slosh of the waves and wake. Amazingly, all went off smoothly despite some extreme rocking, and I settled back into the cockpit and gave the engine some more gas.

Just as I reentered the line of traffic heading in, the engine sputtered and died. With a head boat speeding up astern, I immediately unfurled the jib and beared off. A few seconds later, under the immediate pressure of the sail filling on port tack and slatting in the cross chop, the lower shroud’s turnbuckle gave way. Almost as quickly, I pulled the tiller towards me, bringing the jib around and taking the pressure off the port shrouds. Within a few seconds more, I had the engine restarted, the jib refurled, and was coming around once again, reentering the line of traffic. Fighting the outgoing current and rocking through fifty degrees or so in the passing wake, I assessed my options should the engine die again. The options were none too good: either tacking through the busy, narrow channel against the tide without one of the lower shrouds, trying to restart the engine again right there, or turning around and sailing back out and trying to get the engine started again out there. Fortunately, the engine purred along and I made it into the harbor and anchored in the shallower water to the south of the Corinthian Yacht Club, near a few moored boats, on the opposite side of the Coast Guard station from the normal cruisers’ anchorage.

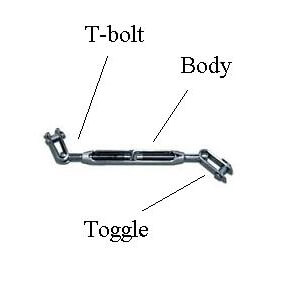

With the anchor down, I cleaned up the boat and looked at the lower shroud. As I suspected, the T-bolt had separated from the body. The surprise was that the T-bolt itself was nowhere to be found. It must have slipped out of the toggle and fallen overboard as I bounced in the chop. Fortunately, I had another turnbuckle below and easily replaced the whole thing.

As the sun went down, I poured myself some of my nearly exhausted supply of Sebastian’s rum and thought over the events of the day. Initially, I was fairly despondent. After all, in my rush to get underway, I failed to properly prepare my boat. Even more importantly, when I realized the shroud had a lot of slack, I did not fully recognize the possible ramifications and failed to take action. I certainly learned some lessons through the experience: 1. while things like brightwork can be left undone and important but not absolutely essential systems such as the head can be inoperable when getting underway, critical things like rigging, the engine, thru-hulls, and the like need to be in good working order and thoroughly tested. 2. while underway anything that does not look right, and even everything critical that does look fine, should be checked out and fixed immediately lest it create a far greater calamity. But what was really bothering me as I sat there in the harbor was that despite seeing the slackening shroud, I did not “pull over” and fix it. What was I thinking? In part, I was not fully thinking. I did not recognize the possibility that the turnbuckle could get free. Instead, I thought the worst outcome was an improperly tuned rig. It was (and is) clear to me that I still had a lot to learn and also needed to be more cautious and thorough. And hopefully those lessons are well learned.

As I continued to think through the day and sip on my rum, my outlook improved slightly. I realized I made a series of good decisions in the moments when the engine died and the turnbuckle came off. I had thought quickly and clearly, preventing further mishap. Moreover, I had also just sailed 65 miles by myself and was now sitting in Cape May Harbor. Despite the events, that was something. Finally, Sebastian’s is the finest rum anywhere, and I had just enough for a second glass.

I would love to hear people’s advice about what I should have done differently and how to avoid such boneheaded lapses in judgment in the future.