Heading south, each evening I would go over the ground we were to cover the following day on ActiveCaptain and make notes on each hazard we might encounter. Most days, the crowdsourced information on ActiveCaptain indicated there were about a dozen areas of shoaling that we needed to be wary of. Much of the advice on the site suggested favoring one side of the channel or another while passing through the problem areas. The next day, I dutifully waited for each troublesome section and carefully stayed off to the supposedly deeper side. Continuing down the Intracoastal Waterway in this manner, we never had a problem.

While we always found sufficient water, I began to wonder whether some of these spots where people had run aground and then reported it to ActiveCaptain were really in the channel at all. Oftentimes, the supposed shoaling areas were in sections with stiff current that could have pushed people out of the channel if they were not paying attention to both the markers ahead and behind. In the case of others, the shoaling was reported on the inside of a sweeping bend in the channel. With the strong tidal currents, the waterways act a lot like rivers, albeit ones that switch direction every six hours; the current gouges out a channel on the outside of bends and deposits silt on the inside of the same turns where the current is more slack. Someone who was just transiting in straight lines from one marker to the next without paying attention to the natural curves of the creek or river the ICW was in might cut right over one of these inside bars.

As we proceeded further down into South Carolina and then Georgia, I seemed to find more circumstantial evidence supporting my suspicions that not all the hazards noted in ActiveCaptain were actually something a conscientious boater needed to concern themselves with. However, I did not find any truly hard evidence until our very last day, as we transited St. Andrew Sound between Jekyll and Cumberland Islands in Georgia.

Earlier that day, we had left the Frederica River just off St. Simons Island. As we made our way into and through Jekyll Creek, we encountered some readings in the low seven feet range shortly after low tide. Having shrimp boats with their booms extended out on either side taking up a good deal of the channel, we had to slowly creep south to Jekyll Island Bridge.

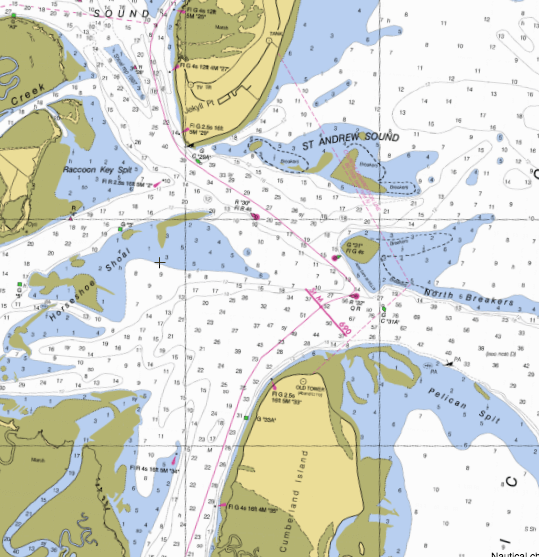

Seeing as how we had barely made it through that part of the ICW, I became a bit more nervous about St. Andrews Sound, which had promised to be difficult. On ActiveCaptain, the northern half of the sound was littered with shoaling hazard markers, indicating Horseshoe Shoal to the west was extending towards the ocean and that the shallow areas to the east of the channel were encroaching further in. But the most troublesome part seemed to be around red marker “32,” which we would round right before passing into much deeper water. Numerous people had revealed they had trouble finding sufficient water in this area. Since it was at the furthest point seaward in the channel and we would be passing within an hour and a half of low tide, I worried that we might run aground and then be bounced around by wave action from the ocean.

While baitfish and shrimp schooled around us in immense numbers and dolphins, seabirds, and shrimp boats all circled them, we carefully made our way out into the sound. More vigilant than ever, I was constantly checking my chart and using the binoculars to locate the various channel markers and ensure we were still in the channel with the strong flood current pushing us westerly. Perhaps because of this attentiveness, I never saw anything less than twenty feet until we reached the charted fifteen feet near G “31,” despite it being close to low tide. As we neared R “32” and the swells got a little heavier, the depth sounder started showing readings just over ten feet. However, within a few moments, we rounded the marker and were safely, and suddenly, in fifty feet of water.

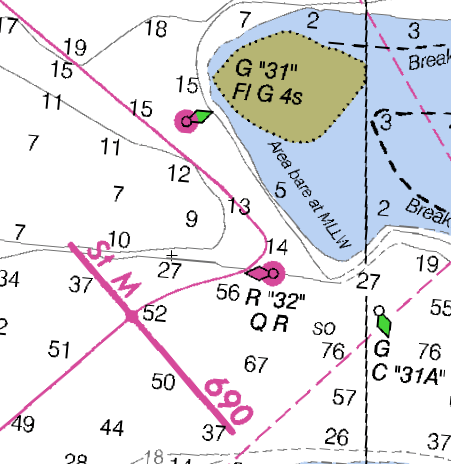

As we began what was a beautiful trip around the inside of Cumberland Island, I read the comments about the shoaling at R “32.” Looking again, it became apparent that many of the people who had problems noted that they passed to the west of “32.” So, the reason they found only five to seven feet of water in this section was because they were actually outside the channel. And why did they go outside the channel? Because, as many of them stated, presumably proud of their seamanship, they were following the “magenta line.” I am not sure why anyone would blindly follow the magenta line noted on the charts – and if you look here, the magenta line actually goes west of R “32,” outside the channel – rather than read the water and honor the actual marks, but that is the blind faith that people put in their chartplotters and paper charts.

The magenta line itself is created by the US Coast Survey. However, the Coast Survey have noted problems with it and even began removing it from some ICW charts. Even if there were no systemic problems with the magenta line, I would treat it like anything else found on a chart, knowing there is always the possibility of human error in its creation or the chance that actual conditions have changed since the chart was made. As I noted in my first post about navigating the ICW, I think charts and chartplotters are useful, but they are some of the last – and least reliable – resources that I turn to when navigating. And, even after confirming that some of the hazards on ActiveCaptain are not actually in the channel, I still think the site is an incredible resource. I would rather be transiting areas with heightened caution because of an erroneous comment on ActiveCaptain than run aground because I had not heeded the advice found there. Of course, like any single resource, ActiveCaptain should not be taken as gospel, even though – or perhaps exactly because – it is crowdsourced.

Great posting. I have to say that I agree with your experiences.

I’m the software developer behind ActiveCaptain and the person who verifies and validates all hazards and anchorages. I’ve personally evaluated each one that has been entered. I also read every comment written on every hazard to determine if some of the details need to be updated because of dredging, aid-to-navigation replacement, or other factors. At this moment, there are about 3,000 active hazards throughout the world listed.

I myself had a funny experience heading north on the ICW last spring in North Carolina. I knew that I had just deleted a hazard because multiple people had written that first, there was a dredge onsite, and then the dredge was gone and depths were over 12 feet MLW. The previous details and comments suggested staying to the red side to avoid the hazard.

So I’m heading north on the natural green side. We’re approaching the place where the hazard used to be, right at the opening to an inlet. Ahead of me is another boat who is quite obviously moving over the the red side for no traffic or apparent reason – they simply hadn’t synchronized their offline ActiveCaptain in whatever app they were using.

I think that type of thing can happen from time to time. I don’t think it’s bad. And like you pointed out, I’d rather error on the side of everyone slowing down and evaluating their surroundings than see a boater blast through and possibly get caught. There are some hazards that I know are on long straight stretches of ICW where staying in the channel will keep you in deep water. But a prevailing easterly wind continually pushes all boats to the western side of the channel. When the area just outside of the channel is sharply shallow, I allow a hazard there even if it’s clearly charted as being shallow. If anything, it keeps everyone alert and inside the channel.

NOAA themselves are licensees of ActiveCaptain today. They found our data was earlier and more reliable than the other sources they were using. Many studies on crowd-sourced information show that in a community of like-minded people, it creates the best data possible.

But we’re not done. We’re working on automated position and depth recording when you’re within proximity of a hazard. That’ll give some objective measurements of what boats ahead of you actually experienced. We’ll be adding that for anchorages too showing where each particular boat anchored and the depth swing they experienced over the X days they were anchored there. All of that will be overlaid with your relationships to sort the data by your friends or group members first.

Each step along the ActiveCaptain journey will hopefully refine all of this and make it better. But it all starts with couples like you who are really out there, cruising, and adding to the data. Thanks for being a part of it.

Cheers!

…Jeff

Thanks for the wonderful, informative reply, Jeff. Your plans for ActiveCaptain sound very exciting. The automated recording information sounds like an excellent plan. I had been thinking about how easy it would be to go into some of the shallower sections such as Hell Gate and Field Cut with a Boston Whaler, a good depth sounder, and a GPS and map out the bottom. But what you are suggesting is easier still and far more comprehensive, crowd-sourcing at its best it seems. We would love to beta test some of the gear if you are looking for folks. I am anxious to hear more about this project as it develops and, especially, reap the rewards in better information. Thanks for all your work on ActiveCaptain and your great response here.

I just now ran across your blog. I’ve been running up and down the ICW now for the past six years and have found Active Captain invaluable even though some of the posts are obviously wrong where the captain had wandered out of the channel. However, I’ve found most of the posts worth paying attention to since the ICW does change rapidly.

In your post you particularly mentioned the turn around R32. When I came through the area the first year I payed particular attention to honoring the buoys, I was not pleased with the shallow water down to 6 ft at low tide, especially with wave action. Eventually I settled on following the 12 ft contour line starting where the magenta line touched the 12 ft mark on your chart and then continuing on the 12 ft line heading due south. For the last five years the depths have not changed, 9 to 10 ft minimum at low tide. This path is to the west of R32 so I take exception to the explanation that captains ran into shallow water by going west of R32, that has not been my experience. Just this summer, the Coast Guard finally moved R32 further to the west acknowledging the encroaching shoal from the east although still not as far west as the path I routinely take – but perhaps enough west for most people.

I’ve found that the Coast Guard pays attention to the posts, moving R32 is one such example. Another example is at Fields Cut. The middle of the channel at the northern entrance is shoal and many boats went aground there. Two years ago after many posts about a good channel at the extreme green side, the Coast Guard stationed a red buoy to guide boaters past the shoal that we all knew about anyway if we read Active Captain. The added red buoy is so far to the green side that some boaters thought it was off station and went aground anyway (those that didn’t ready AC).

Alas, there’s no help for Hell Gate just south of Savannah. I came through this fall at 2 ft over low and plowed mud for about 100 ft but made it through with my 4 ft 9 in keel.

There’s a 10 ft MLW path through the shallows just south of Fernandina but you have to know the directions, the buoys do not point the way, AC provides help.

So I pay attention to all the post and ignore the ones I know to be problematic and I post regularly on Active Captain, it’s a good resource.