For a lot of people, myself included, being on the water, especially on a sailboat, represents freedom. Powered by the wind, you have the ability to go anywhere, whether it be across the bay or across an ocean. Moreover, while there are rules on the water, the restrictions are fewer than on land and most relate obviously and directly to the safety and well-being of yourself and others. And there are so many other ways that people gain a sense of freedom by being out on the water, beholden to little more than the breeze.

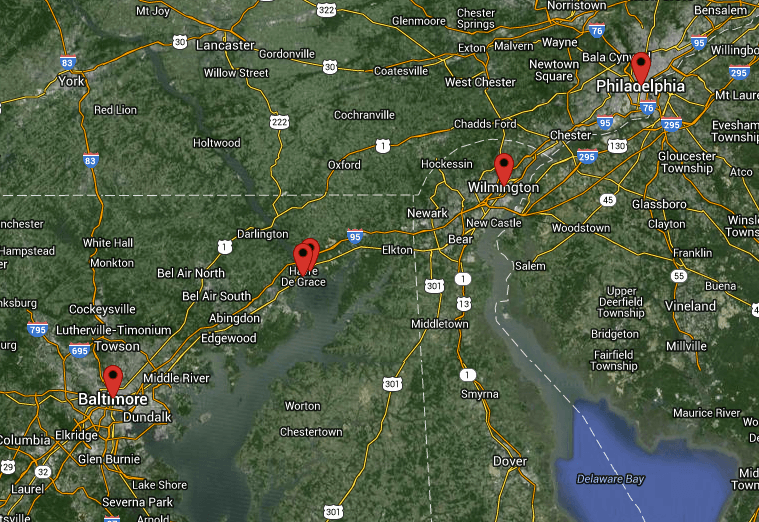

On Bear this summer, I not only had the opportunity to reflect on how sailing offers freedom to me personally, but I also spent some time thinking about the ways sailing, at times, offered freedom to slaves as well. These thoughts began as we entered the Chesapeake, passing by the mouth of the Susquehanna River near Havre de Grace in the northern part of the bay. It was there that Frederick Douglass, having come from Baltimore by train, crossed the Susquehanna between Havre de Grace and Perryville on his escape to the North. In Perryville, he again boarded a train, this time to Wilmington in the then slave state of Delaware. From there, he took another boat on to Philadelphia and freedom.

Throughout his travels north, Douglass did not actually sail any portion of the route, having rode steamboats across the Susquehanna and up the Delaware. However, he did disguise himself as a tar and, using “a sailor’s protection” – a document, short of freedom papers, but meant to identify free seamen in ports around the world – passed himself off as a free man of color. As Douglass made clear in his last autobiography, Life and Times of Frederick Douglass

, the document and dress only offered him a modicum of protection, and he could have been detained at any moment. But “the kind feeling which prevailed in Baltimore and other seaports of the time, towards ‘those who go down to the sea in ships,’” aided him greatly. The nation was young, and, as such, still heavily dependent on maritime commerce, not to mention only twenty years from the War of 1812, fought in part over British impressment of American seamen. In such an environment, sailors, even black ones, commanded a certain amount of goodwill from other citizens. Consequently, nobody carefully inspected Douglass’s papers or interrogated him about his trip. Had anyone done so, Douglass believed his true identity would have been discovered, despite the fact that Douglass “knew a ship from stem to stern, and from keelson to cross-trees, and could talk sailor like an ‘old salt’” from his days laboring in a Baltimore shipyard. Fortunately for Douglass, and America, his association with the sea facilitated his escape, freeing one of the greatest intellectual and abolitionist voices of the nineteenth century.

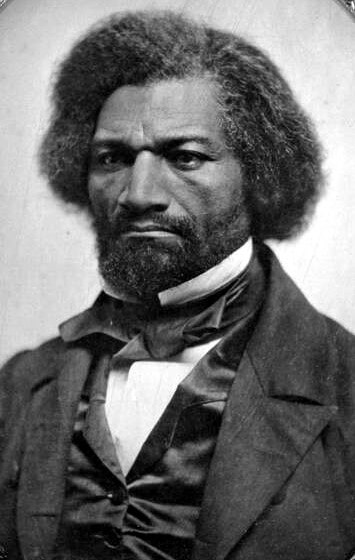

Frederick Douglass in 1856, 18 years after his escape, from Wikipedia

Of course, there were other ways that slaves used the sea and sailing vessels to escape their bondage (and Douglass himself sought out , which I continued to ruminate on as we spent the summer on the Chesapeake Bay and pushed further south along the Intracoastal Waterway. Tomorrow, I will talk a little more about the more obvious use of sailing vessels in this task, as a direct means of deliverance. And, maybe sometime down the road I will ponder all the reasons why Douglass initially made his home in the whaling capital of New Bedford after heading north from Philadelphia.