Slaves gained freedom on and from the water in a variety of ways, not just stealing themselves away on sailing vessels. For instance, we have already seen how Frederick Douglass disguised himself as a sailor to escape to the North. But slaves claimed and enjoyed additional liberties working on board ships, even when they did not free themselves from the institution of slavery itself. Serving their masters on board boats, many slaves found that the way of the ship offered them opportunities to enjoy freedoms, even the possibility of temporarily lording over whites, that they may not have had on land. Of course, enslaved black seamen, no matter how many liberties they enjoyed at sea, were still not only chattel, but also subject to acts of racism and, like other white sailors, the capriciousness of the ship’s officers.

John Singleton Copley, Watson and the Shark, from the National Gallery of Art

Margaret and I had intended to head up the Potomac River to Washington, DC this summer – before weather and the vicissitudes of our trip prevented us – in part so that we could view the above painting at the National Gallery of Art. The American John Singleton Copley painted the image, “Watson and the Shark,” for Brook Watson, who was depicted as the shark’s intended victim. Based on actual events that occurred earlier in Watson’s life in Havana Harbor, Cuba, Watson worked with Copley to ensure that the painting accurately represented the singular event in Copley’s life. Saved by his shipmates, including the black seaman, Watson went on to amass a small fortune in the shipping industry. The image attests not only to Watson’s humble beginnings and deliverance, but also to the relative equality of men at sea. The black sailor is an integral part of the rescue effort and, moreover, close friends with Watson, like the others in the dory. The position of this one black seaman was not at all unusual during the 18th and 19th centuries, as life aboard a ship provided free blacks and, especially, slaves, an escape from the more oppressive discrimination found on land and a measure of freedom in the structure of command aboard sailing vessels of the era. Thousands of enslaved blacks shipped out on coasting and high seas voyages, serving alongside whites where they were less judged by the color of their skin and treated on the basis of their race, and more by their seamanship skills and rank aboard ship.

Some slaves gained even more freedom at sea, rising to command others. Whereas on land a black man, whether slave or free, would never be tolerated in a position of power over whites, it occurred occasionally on the water. Jeffrey Bolster, in his fabulous history, Black Jacks: African American Seamen in the Age of Sail

, from which I take the rest of this post, points out that many of the pilots in the southern ports that we passed through this summer were enslaved sailors during the nineteenth century, commanding ships, and their white captains and crew, over the tricky shoals into the Pamlico and Albemarle Sounds, through the strong currents on the Savannah River, and into the busy harbor at Charleston. In an upending of traditional racial dynamics, the position allowed these individuals great power, including the freedom to order and, if necessary, berate others on board. Bolster allows that one enslaved Martinique pilot did the latter when, after being ridiculed for his dress by a white sailor, the pilot asked, “Who you laugh at, you bloody bitch?” asserting his authority and demeaning the white sailor in a way that would have resulted in the slave’s death, or at least a severe beating, in any other situation.

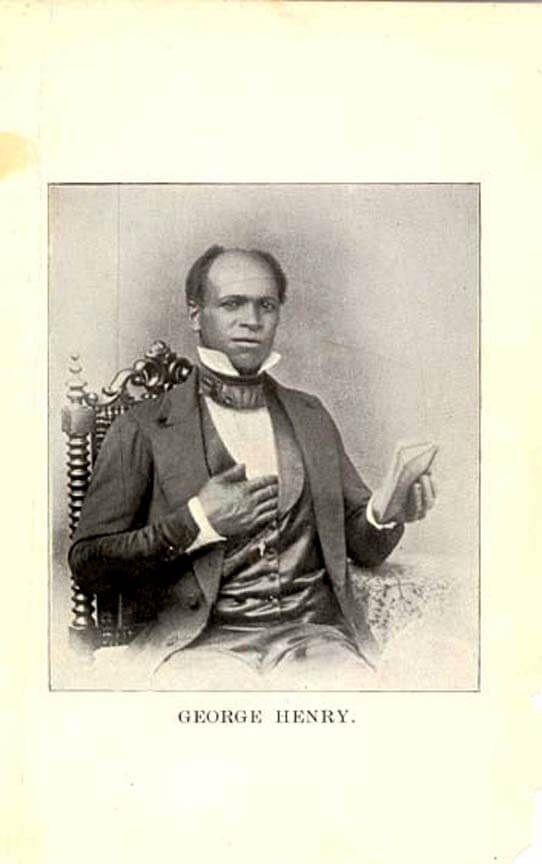

Numerous masters also entrusted command of their coasting ships to their slaves, and these enslaved captains found a degree of liberty and self worth in their leadership, abilities, and accomplishments. One Moses Grandy plied the waters to the east of the Outer Banks (and also helped build the Dismal Swamp Canal…his autobiography is here), hauling lumber and other goods for his owner. Anyone who has ever passed up the Alligator, Neuse, or Pungo Rivers in an auxiliary craft today can only imagine the skill, local knowledge, and savvy that must have been involved in navigating these waters under sail in a heavily laden vessel two hundred years ago. Grandy accomplished all this and more, relishing his relative freedom and successes on the water. On the Chesapeake, an enslaved schooner captain, George Henry, not only enjoyed his merited role and the freedom it brought, but also delighted in sharing information about the places he had seen with his land-based relatives and friends, who endured the more traditional slave experience. He later said that he returned from the sea the first time “with knowledge to impart my friends, and with double zeal to increase my knowledge of the world.” While still a slave, Henry found that the sea gave him access to new worlds and a respected position within his community. He also took great satisfaction in his work, proudly describing how “we would have gone on [a] lee shore, and the vessel and all hand would have been lost” if not for his quick actions and how he “took a delight in having everything put in first-rate order” on a new vessel that he outfitted.

George Henry, from his autobiography

The freedom that enslaved blacks could enjoy on the water never completely made up for their status as property or entirely sheltered them from racist words and actions, but the sea could provide a good deal of liberty, making their lives slightly more endurable and, even, rewarding. Today, when we go out on the water, it is with different, but not dissimilar motivations to gain some sense of freedom, escape the land-based stresses, experience new things, and develop a heightened sense of self.