As a kid, there were several summers when my buddy Steve and I were inveterate fishermen and crabbers, heading to the club docks with pole and trap whenever we were not out sailing. We’d fish for anything that we could catch – and we caught everything – with a few crab traps out as well. Our crab bait of choice was bunker, not yet having been indoctrinated into chicken necks as a nine or ten-year old. That experience with bunker – buying it out of the huge freezer at the bait and tackle shop, cutting it into thirds, and, as often as not, dissecting what was left – made me a lifelong fan of the fish, and I have become more and more obsessed – as I am with a lot of animals – with the lowly bunker.

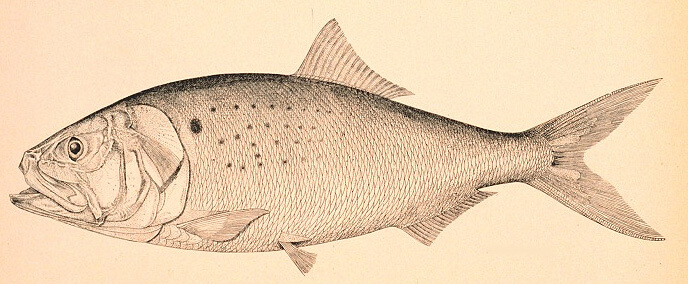

I have vague memories of the battle to save the striped bass up and down the East Coast in the 1980s and how that fight was, in part, about improving the numbers of bunker, which is a major part of the striped bass diet. It was a successful struggle, but the striped bass – and the bunker – are still in danger, which is probably not a surprise. My memories of those events were considerably stoked and refreshed over the last few years as I read Dick Russell’s engaging Striper Wars , which chronicles much of the 80s fight, the science of striped bass and menhaden (the formal word for bunker, adapted from the Narragansett word for the fish – and for fertilizer – munnawhatteaûg) and the continuing threats to both. Together with H. Bruce Franklin’s The Most Important Fish in the Sea: Menhaden and America , these books impressed upon me the critical importance of bunker in the food chain and the ways that we are putting a major stress on the population.

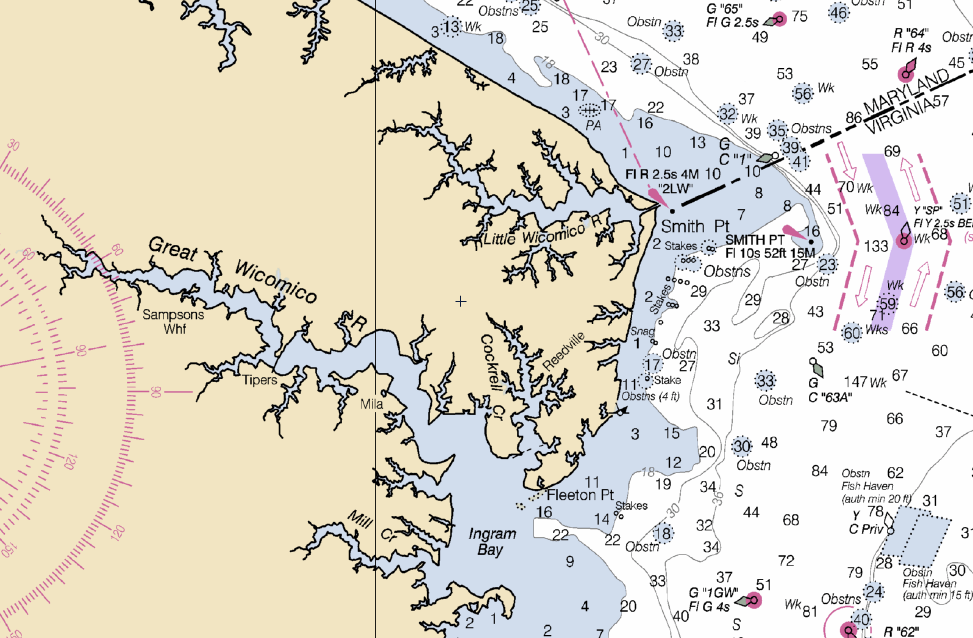

With all this in mind, it was a depressing and smelly, though exciting, experience to cruise up the Great Wicomico River and pass Reedville, Virginia, during our first summer in the Chesapeake on Bear. Reedville is the center of the menhaden fishery where the vast majority of the 400,000-plus metric tons of commercially harvested menhaden are landed every year. As we passed by, several gigantic factory ships were at the dock or moving around, and the next day, while we left the Wicomico, we had the pleasure of experiencing the overwhelming smell of the processing plant as the wind blew lightly from the north. As the stench infiltrated every pore in our noses, it drove home the point that our bunker – and with them, a great deal of the health of our coastal ecosystems – are being stripped from the ocean just so that we can feed our cats Fancy Feast and get our Omega-3s from fish oil pills, which are the two chief uses for the unpalatably oily menhaden.

This summer, we once again encountered menhaden in large numbers, but this time the fish were swimming free. While making our way across Long Island Sound, my Dad and I saw massive schools of bunker in both Port Jefferson and Oyster Bay. On the dinghy, we cruised through the schools, which moved just out of reach of our outstretched hands. At times, there were so many fish around Bear in the evening, that we could hear the animals breaking the surface from inside the boat.

Later, when we were coming down the Jersey coast, we saw churning balls of menhaden, occassionally hundreds of feet across. I kept thinking about stories I had heard about fishing for stripers in exactly these sort of conditions, putting a weighted treble hook on the end of a line, casting into the school of bunker, snagging a fish with the hook, and then, almost instantly, getting a strike as a bass attacked the injured menhaden. About four miles off Wildwood, with the bunker schools still around us, a huge whale surfaced right in the middle of one of these balls. My Dad and I sat transfixed, watching the whale as it repeatedly breached, feeding on countless numbers of the fish. This is a memory of the bunker – of a magisterial cetacean gorging itself on the fish – that won’t need refreshing, reminding me of just how important the bunker and so many other seemingly lowly creatures are to our environment and our enjoyment of it.